Internet research - I loves it.

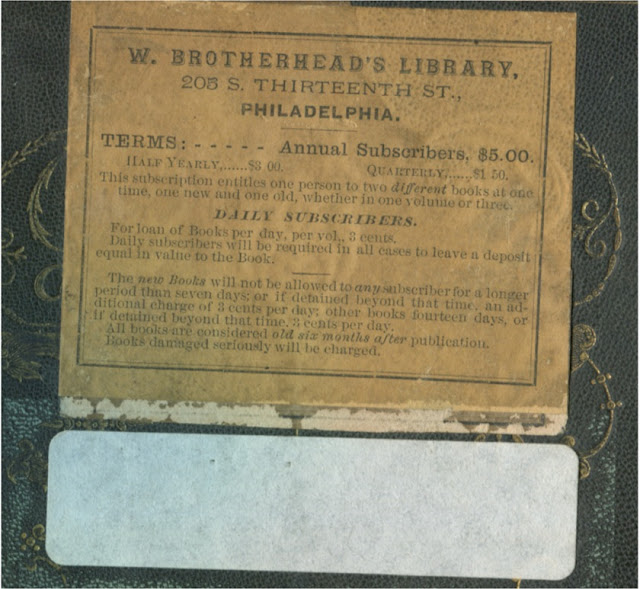

Yesterday's post didn't show all of the book's cover, but you could see a comparatively new piece of tape on the bottom panel of the spine, which carried, handwritten in white, the library call numbers of the book when it was at the University of Waterloo (Ontario), whose card sleeve adorns the inside front pastedown. But they got it from somebody else - I know because on the front cover there is a ticket, about 3" x 3":

I love the peek into past lives I get from reading old advertising, tickets, trade mail, and so on. I can't tell, of course, whether this book was bound specifically for Brotherhead's Library in Philadelphia, or acquired by them sometime after the binding, which could not have been earlier than 1853. I might suspect that the rather grand binding meant it wasn't originally bound for the library, because they would have known the ticket would cover it up. But maybe originally the library didn't use tickets - this may have been the original library book, and the ticket was pasted on decades later.

Just a bit of trivia:

A quick trip to Google brought up Trubner's American and Oriental Literary Record for August 1869, which include a letter from Mr. W. Brotherhead himself. Stung by a previous reference to Brotherhead's library in New York containing a mere 3,000 volumes, he listed the (much larger) number of volumes contained in each one of their major libraries - including the Philadelphia one, with 20,000 volumes, and listing their lending policy, which is the same as on the ticket we have here.

It interests me that on the ticket they spell out a policy for dealing with multi-volume novels (all in the same title count as one) because it shows that the "three volume novel" of fifty years before were still normal to find in a library collection. And I'm sure a lover of business, economics, or social history would make a lot out of the various fees involved - such as, that if you expect to have more than 165 book-days per year you might as well take out the whole year's subscription, and if you have to leave the price of the book as a deposit at the library to take the book out, then the really poor people were essentially barred.

The point of this post? Well, nothing really, except I thought the ticket was a historical artefact worth noting.

You find all sorts of these things in old books. One time I took the spine off a mid-19th century Bible and discovered the mull reinforcing the spine was a piece of cloth from a woman's dress. It was lovely - a pale green flowered lawn - and I realized that if your wife discarded just one dress you had enough mull for dozens of thick Bibles, as dresses back then used a lot of fabric. Another time the spine of a 17th-century book had been reinforced with paper left over from printing a play. I only got a few lines, but it does make me wonder what's inside other books whose spines haven't fallen away.

No comments:

Post a Comment